Why look at animals? asks John Berger in the title of a 1977 essay that examines the historical interdependence of humans and animals. Much of Berger’s eloquent writing centers on the question of looking and the layers of meaning that can be parsed from what we see, and here he begins with how humans and animals look at each other:

'The eyes of an animal when they consider a man are attentive and wary. The same animal may well look at other species in the same way. He does not reserve a special look for man. But by no other species except man will the animal’s look be recognised as familiar.' [1]

When humans look at humans, even if they cannot understand each other’s language, the existence of language in itself allows them to ‘reckon with each other as with themselves’. Between humans and animals, however, is an unbridgeable gulf – ‘an abyss of non-comprehension’ – due to the animal’s lack of language. It is this lack, the animal’s silence, which ‘guarantees its distance, its distinctness, its exclusion, from and of man’. [2]

Looking in and of itself is vital to Alice Neel’s paintings – mostly portraits, almost all of which were painted directly from life, thus subject to the inflections of light, moment or mood that come with the passing of time. But her portraits depend equally on the potential for comprehension that language allows. Talking was always central to her painting process, and was the basis for the empathy and psychological acuity that characterise her work. ‘Before painting, when I talk to the person, they unconsciously assume their most characteristic pose, which in a way involves all their character and social standing – what the world has done to them and their retaliation’, she said. [3] The cumulative effects of a life’s experiences, inscribed in the physiognomy of each of her subjects, were what Neel compulsively sought to capture. Thus, when taken together, her works comprise a broad and insightful study of the human species in modern society.

The painting’s allegorical tenor is typical of Neel’s early work, but here the wolf’s usual allegorical role as aggressor is upturned, as she seems rather to offer protection and companionship to the woman.

Given this resolute focus on humans of all kinds and the ‘abyss of non-comprehension’ Berger ascribes to animals, Neel’s animal paintings are something of an anomaly. They do, however, allow for unique insights. To borrow from Berger again, ‘their similar/dissimilar lives allowed animals to provoke some of the first questions and offer answers […] The first subject matter for painting was animal. Probably the first paint was animal blood’. [4] Unlike Neel’s occasional cityscapes, rural landscapes or still lifes, whose static, almost airless depictions contrast starkly with the animation of her portraits, her paintings of animals offer an illuminating foil to her central preoccupation with humanity. The animals are presented as companions to the men or women we see them with, but their relationships are based more on the difference Berger describes than on anthropomorphising similarity. In this she differs from other mid twentieth-century figurative painters such as David Hockney or Lucian Freud who also often painted animals. It is hard to imagine the steely-eyed Neel devoting as much time and canvas to her pets as Hockney, who in 1995 alone made over forty paintings of his two dachshunds, Stanley and Boodgie. Freud meanwhile made many compassionate drawings and paintings of his whippets, but his paintings of people, especially when naked, are deliberately animal-like in their blunt flesh-and-bone materiality.

The relation between humans and beasts ‘is a companionship offered to the loneliness of man as a species’, [5] wrote Berger; terms which seem singularly applicable to Neel’s depiction not only of humans engaged in the lonely struggle of modern life, but also the role that her painted animals played. This is clear to see in Nadya and the Wolf (1931), which pictures Nadya Olyanova, a close friend and graphologist, seated on the ground before a bleak winter forest, her face a mournful white mask, while the placid figure of a lactating wolf stands before her. The painting’s allegorical tenor is typical of Neel’s early work, but here the wolf’s usual allegorical role as aggressor is upturned, as she seems rather to offer protection and companionship to the woman.

The themes of motherhood and child-rearing that come up here are subjects that recur throughout Neel’s work, but are treated as psychologically complex and physically demanding experiences rather than cooed over with sentimental benevolence. Nadya was also the model for the early work Degenerate Madonna (1930), where she is pictured with distended breasts and smudged features, a ghost-like child on her knee. The alienation and distress this depicts can no doubt be traced to Neel’s own suffering at the death of her first born child in 1927, her estrangement from her second child in 1930, and subsequent nervous breakdown. Shortly after being discharged from a private sanitorium in 1931, Neel visited Nadya and her husband Egil, and a photograph from that visit shows Neel with a nursing dog, suggesting this to have been the inspiration for Nadya and the Wolf. The painting seems to be as much a portrayal of Neel’s own psychological state and conflicted experience of motherhood as a depiction of her friend.

Is the cat an avatar of the artist, startled and vulnerable in the face of this man’s stern, condemning stare?

As this photographic document suggests, even if they appear to be allegorical props or accessories used to augment a gesture, the animals that appear in Neel’s portraits were usually based on real encounters. Given that she painted her portraits almost exclusively from life, the animals that appear alongside sitters were presumably also present, not added in later as pictorial devices. In Eddie Zuckermandel (1948), the Siamese cat sitting on the subject’s lap echoes his upright posture, while its wideeyed stare provides an innocent foil to Eddie’s penetrating gaze, cast deep in shadow but directed right at Neel. Is the cat an avatar of the artist, startled and vulnerable in the face of this man’s stern, condemning stare? The same round-eyed Siamese appears in a 1949 portrait, nestling against the voluptuous naked body of Pat Ladew, a young oil heiress who had commissioned the portrait. The cat, together with Ladew’s black shoes, is the only accessory to her nudity, and coyly points its ear in the direction of the woman’s exposed vagina. Ladew balked at the graphic depiction of the completed painting in the end, first requesting that Neel add underwear, and then when still dissatisfied eventually exchanged it for a still life (on its return, Neel erased the underwear, returning it to its original unabashed state). In both of these cases, the presence of the cat emphasises the overriding atmosphere of the portrait – confrontation in the first, or sensuousness in the second – while acting as a kind of go-between from sitter to artist.

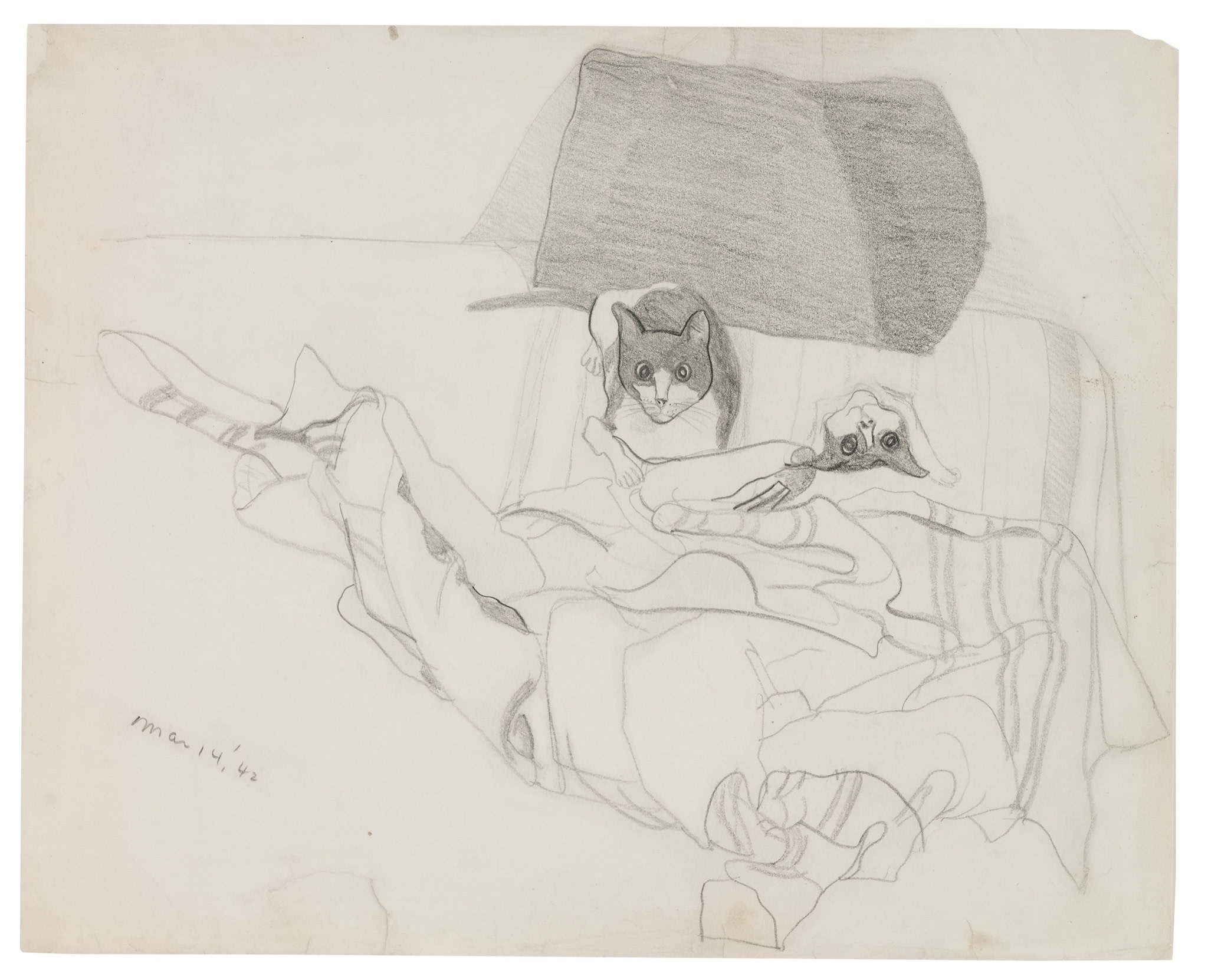

Neel painted her portraits in the living room–cum-studio of the apartment in Spanish Harlem where she lived with her two sons Richard (born in 1939) and Hartley (born in 1941), so the Siamese cat in both of these paintings was probably Neel’s own, having insinuated itself into the portrait session. Or perhaps, as two drawings from around this time indicate, it was one of a pair. The drawings show two sleeping Siamese cats curled up with each other into a single, sinuous, two-headed form.

One drawing dated 1951 is sketched on a piece of lined school paper on which ‘Hartley Neel’ is

written in a clumsy cursive script above the uncompleted sum ‘1/4 + 3/8’. It is tempting to envision this as the outcome of ten year-old Hartley’s homework session with his mother, in which the matter at hand was forgotten in favour of a closely observed study of the family pets.

In Richard with Dog, every inch of the canvas is densely worked, from the background foliage to the floral patterned shirt to her son’s defiant, tight-lipped stare.

It is almost impossible to extricate Alice Neel’s work from her biography, seeing as it concerns itself so directly with the people who were immediately around her, whether her lovers, children, close friends, social acquaintances, famous artists of the time or unknown locals from her neighbourhood. Add to this the intensity of each portrait, and it is hard to get beyond a gut curiosity about the lives of the sitters and their relation to the artist, to consider more formal issues. ‘If I have any talent in relation to people […] it is my identification with them’, she said. ‘I get so identified when I paint them, when they go home I feel frightful. I have no self – I’ve gone into this other person. And by doing that, there’s a kind of something I get that other artists don’t get.’ [6] Beyond this extraordinary ‘kind of something’ and the preoccupation with content it compels, however, considerable stylistic developments can be detected across the five decades of her working life. This is clear in two portraits painted some fifteen years apart, each portraying one of her sons with a pet. In Richard with Dog (1954), every inch of the canvas is densely worked, from the background foliage to the floral patterned shirt to her son’s defiant, tight-lipped stare. The unidentified dog peeking shyly and deferentially from the corner of the canvas is likewise a tight knot of brown, black and white.

In Hartley with a Cat (1969), meanwhile, the figure is loosely defined by fluid lines of colour which sketch out the contours of his striped t-shirt and casually crossed legs. His facial features are picked out in patches of colour that are not blended together but left distinct, while the cat he is clutching almost disintegrates into daubed patches of tabby fur. In many of Neel’s works from this time on, the bold sinuous lines that define figures are no longer studiously filled in as they were in earlier works, and backgrounds are more implied than finished. As the years progressed, a greater economy and distillation of salient features becomes apparent, as if Neel was zeroing in ever more effectively on the crux of each likeness.

Of all the animal paintings here, this portrait of Lushka comes closest to Neel’s portraits of people. The dog is relaxed, centrally positioned and meets Alice’s look with its own steady gaze…

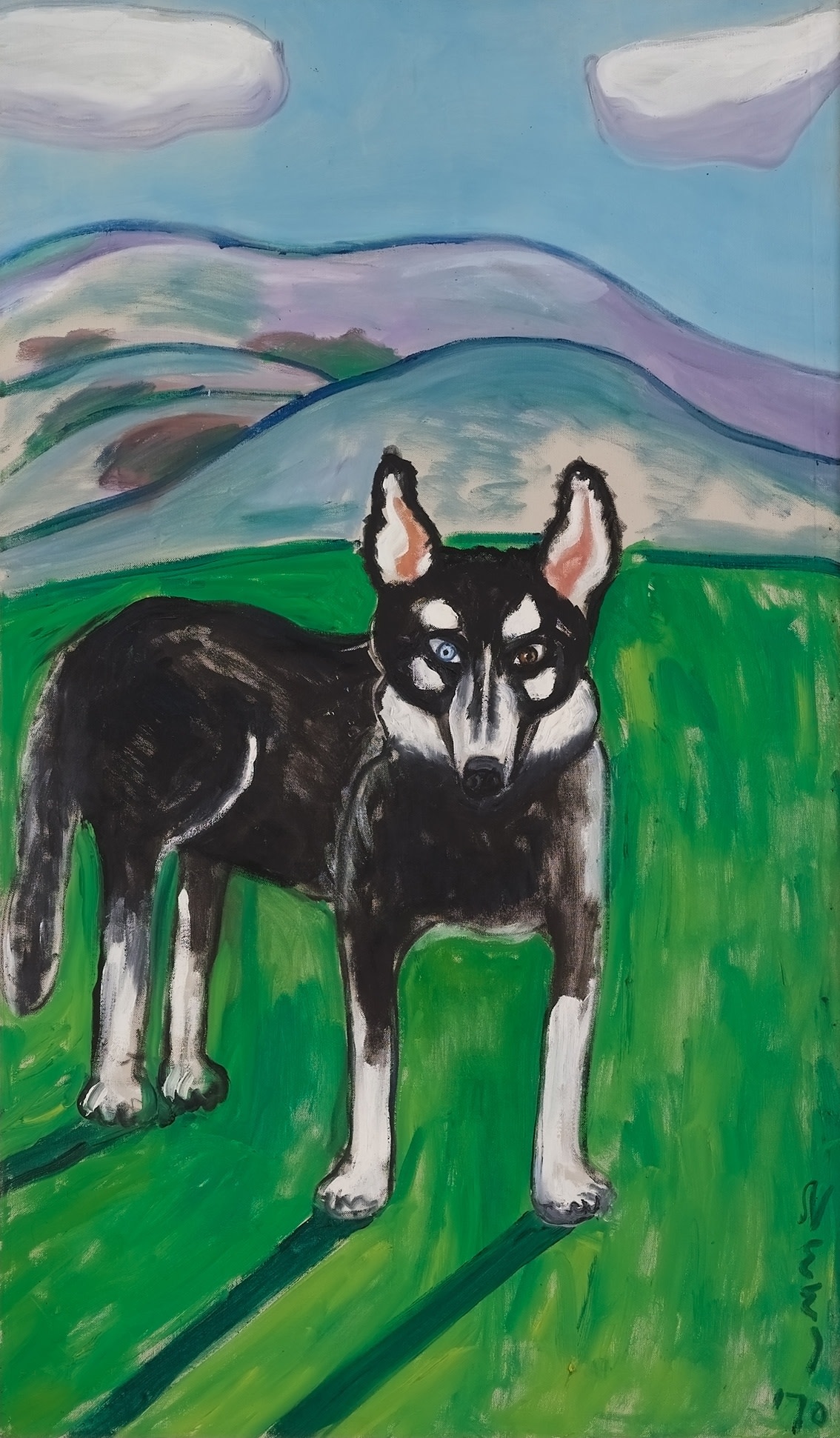

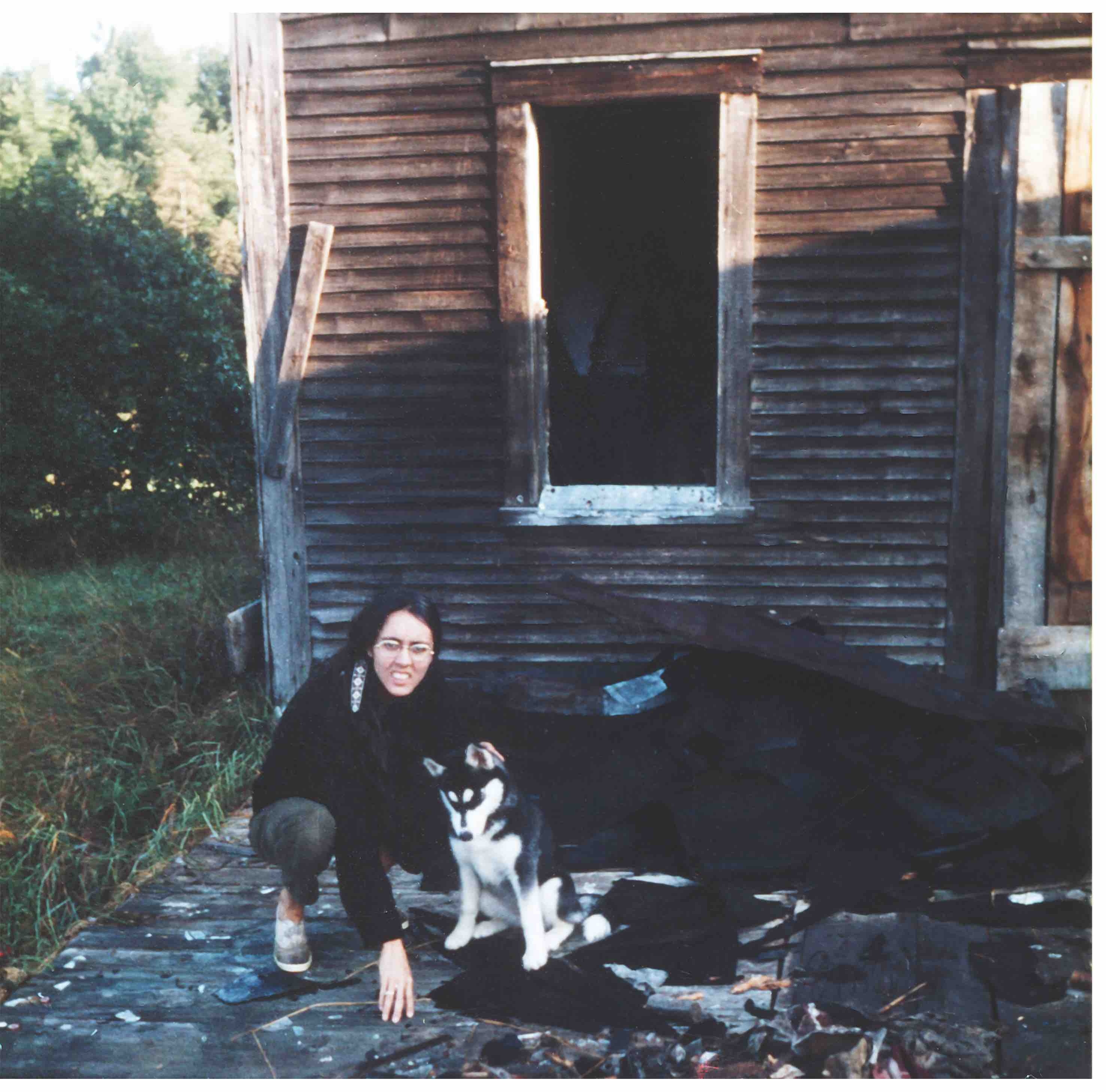

Lushka (1974), a compelling painting of Hartley and his wife Ginny’s husky, which was painted five years later, is unusual within this trajectory given that the whole surface is covered, and subject and background are worked evenly, if not luxuriantly. But its looseness of gesture and unmodulated brushstrokes are apparent when compared with the portrait of Richard painted twenty years previously. Of all the animal paintings here, this portrait of Lushka comes closest to Neel’s portraits of people. The dog is relaxed, centrally positioned and meets Alice’s look with its own steady gaze, approaching the psychological articulation of her other works. But the dog’s envelopment in the landscape of leaves, rocks, trees and patchy grey sky suggests it rather to be an intermediary between man and nature, as is even more the case in the earlier symbolist-inflected, more schematic painting of Lushka from 1970 with its bold, Munch-like colours.

A good proportion of Neel’s paintings featuring animals are outdoors. Some, like the 1947 Gouray, were painted in Spring Lake, New Jersey, where she bought a property in 1934, going on to spend part of every summer there for the rest of her life.

Later, works such as the 1974 Lushka were painted at the farm in Vermont to which Hartley and Ginny moved in 1973. In the country, away from ‘the awful struggle that goes on in the city’, [7] and its inexhaustible population of possible sitters, animals could come into their own.

When temporarily removed from the urban rat race and the need for survival, Neel’s way of looking at the world shifts markedly in cadence. Here it can admit animals, plants and vibrant shades of green…

John Berger writes that after looking at a work of art, ‘what we take away with us – on the most profound level – is the memory of the artist’s way of looking at the world’. When temporarily removed from the urban rat race and the need for survival, Neel’s way of looking at the world shifts markedly in cadence. Here it can admit animals, plants and vibrant shades of green rather than the drab greys and mauves of the oppressive cityscapes she painted around this time, and the dark lines inscribed by experience on the faces of city dwellers. Despite her regular rural respites, however, Neel never left the city for good. She lived her whole adult life in Manhattan, immersing herself in its intensity and dedicating her life’s work to the ravages of urban life. Viewers of Neel’s work are faced, quite literally, with her way of looking at the world, and assume her place opposite the sitters or scenes depicted now in paint on canvas. ‘At least I tried to reflect innocently the twentieth century and my feelings and perceptions as a girl and a woman’, she wrote in a personal statement in the late 1970s, quickly adding ‘not that I felt they were all that different from men’s’. [8]

Kirsty Bell is a freelance writer and contributing editor of frieze, based in Berlin, Germany.

1 John Berger, ‘Why Look at Animals?’ in About Looking, (1977, New York: Vintage International, Reprint edition, 1991), 4-5.

2 ibid. 6.

3 ‘Statements by Alice Neel’ in Alice Neel. Pictures of People, (Berlin: Aurel Scheibler, 2007), 19.

4 Berger, 7.

5 ibid. 6.

6 Alice Neel. Pictures of People, 19.

7 Alice Neel in Alice Neel, dir. Andrew Neel (New York: SeeThink Films, 2007).

8 Alice Neel. Pictures of People, 22.

This essay was first published to accompany the 2014 Victoria Miro exhibition Alice Neel: My Animals and Other Family which featured paintings and works on paper on the theme. It appears in the accompanying catalogue along with illustrations of all works included in the exhibition.

About Alice Neel

One of the foremost painters of the twentieth century, Alice Neel (1900–1984) produced a body of work that is intimate, casual, personal and direct. Throughout her life, Neel developed a unique talent for identifying particular gestures and mannerisms that reveal the singular identities of her sitters. Hers is an art characterised by honesty. Alternating between sombre and vibrant colours, Neel's application of paint could be hard-edged and broad as she addressed her subjects on canvas without preliminary sketches. The result of this direct approach is a body of work that preserves the spontaneity of initial ideas and the liveliness of the one-to-one encounter.

Images from top:

Lushka (detail), 1974

Alice and her lover Kenneth Doolittle in a quiet moment with one of Alice’s cats, c1932

Nadya and the Wolf, 1932

Alice in the garden of Nadya Olyanova’s country house, c1931. The German Shepherd may

be the model for the wolf in Nadya and the Wolf

Eddie Zuckermandel, 1948

Pat Ladew, 1949

Two Cats, 1942

Richard with Dog, 1954

Hartley with a Cat, 1969

Lushka, 1974

Lushka, 1970

Alice’s daughter-in-law Ginny with Lushka, c1970, in front of the abandoned cottage on the grounds of Ginny and Hartley’s home in Vermont, which Alice later renovated for her studio

Carol with a Dog, 1962

Gouray, c1947

Mother and Child, c1936

All works © The Estate of Alice Neel, courtesy The Estate of Alice Neel and Victoria Miro