Njideka Akunyili Crosby had already honed her method when she turned her attention to making the works that would become this series. Her signature technique was in place. A combination of painting, drawing, and acetone transfers of photographs and found images on paper, it yielded large-scale works that exhibited, to striking effect, the dual pull of formalist composition and a collagist’s verve and spirit of detail and exploration.

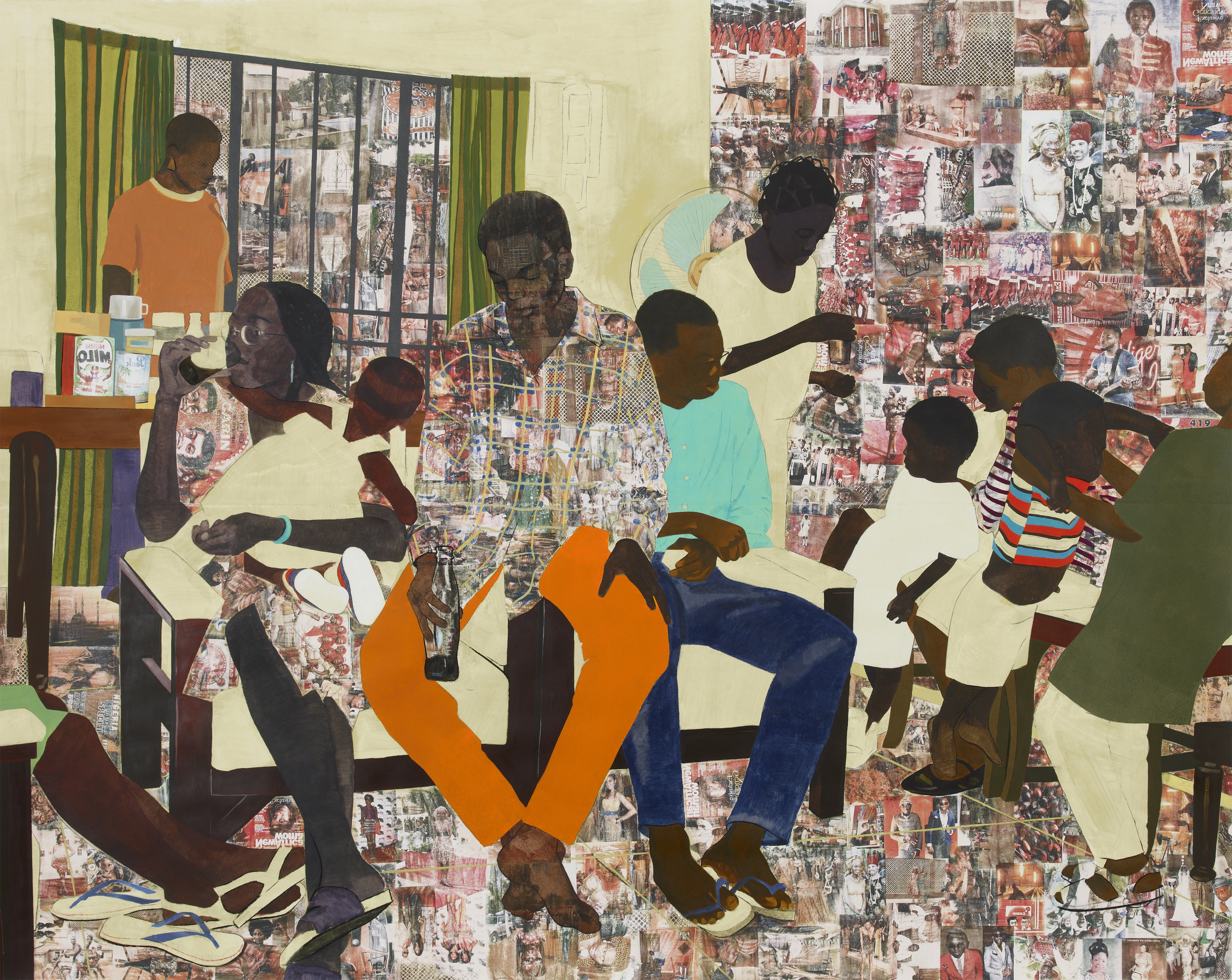

She has put this language to enthralling use, notably in her treatments of middle-class, provincial spaces that she knows from her childhood in, and her subsequent return visits to, the city of Enugu in eastern Nigeria. These modest but sturdy interiors feature simple, angular geometries that she gently destabilises with stretches of image transfers that float off walls or floors onto objects and figures. The effect is to invoke an alternate planar system governed by a complex mathematics of memory. In these calibrated microcosms, Akunyili Crosby’s diptychs and multi-figure works look in on scenes in the life of people much like herself, families much like her own. She renders archetypal encounters – the visit from abroad, the journey to the village, the gradual enfolding of a white husband into an African family – with a tender calm that results from knowing that culture is allusive more than didactic; that even big moments are wrapped in the quotidian.

It is perhaps the most specifically Nigerian of Akunyili Crosby’s projects.

Though it adheres to this mindset – and is made using the same techniques – “The Beautyful Ones” series pursues a particular agenda. It is perhaps the most specifically Nigerian of Akunyili Crosby’s projects. For one thing, it subtracts the layer of cross-cultural negotiation that otherwise (and reasonably enough) invites the viewer to seek connections to the artist’s narrative of migration, from Enugu to Lagos to studies in Philadelphia and New Haven to married life and motherhood in Los Angeles.

Here, instead, the journey is in time. “The Beautyful Ones” are children, subjects whom Akunyili Crosby has landed on in her photo archive (and thus often from her family, but not solely). Extracting them from the original context, she renders them in painting, then restitutes them into her trademark settings, in which not only the background mosaic of image transfers, often from vintage magazines, but also elements of the composition – a party outfit, a particular model of doll, a Peugeot 504 sedan, an old-fashioned television cabinet and stereo set – concentrate the bulk of their allusions on the 1980s and 1990s.

For Akunyili Crosby, born in 1983, this is memory work – certainly in the case of “The Beautyful Ones” Series #1c, featuring her sister; “The Beautyful Ones” Series #2, featuring her brother; “The Beautyful Ones” Series #4, featuring her second sister; and “The Beautyful Ones” Series #5, which, jumping back a generation, takes as point of departure a childhood photograph of their late mother, Dora Akunyili. (The latter photograph is rendered in full in Mama, Mummy and Mamma (Predecessors #2), 2014 (pictured, below), one of the myriad small cross-references that stitch together Akunyili Crosby’s body of work.)

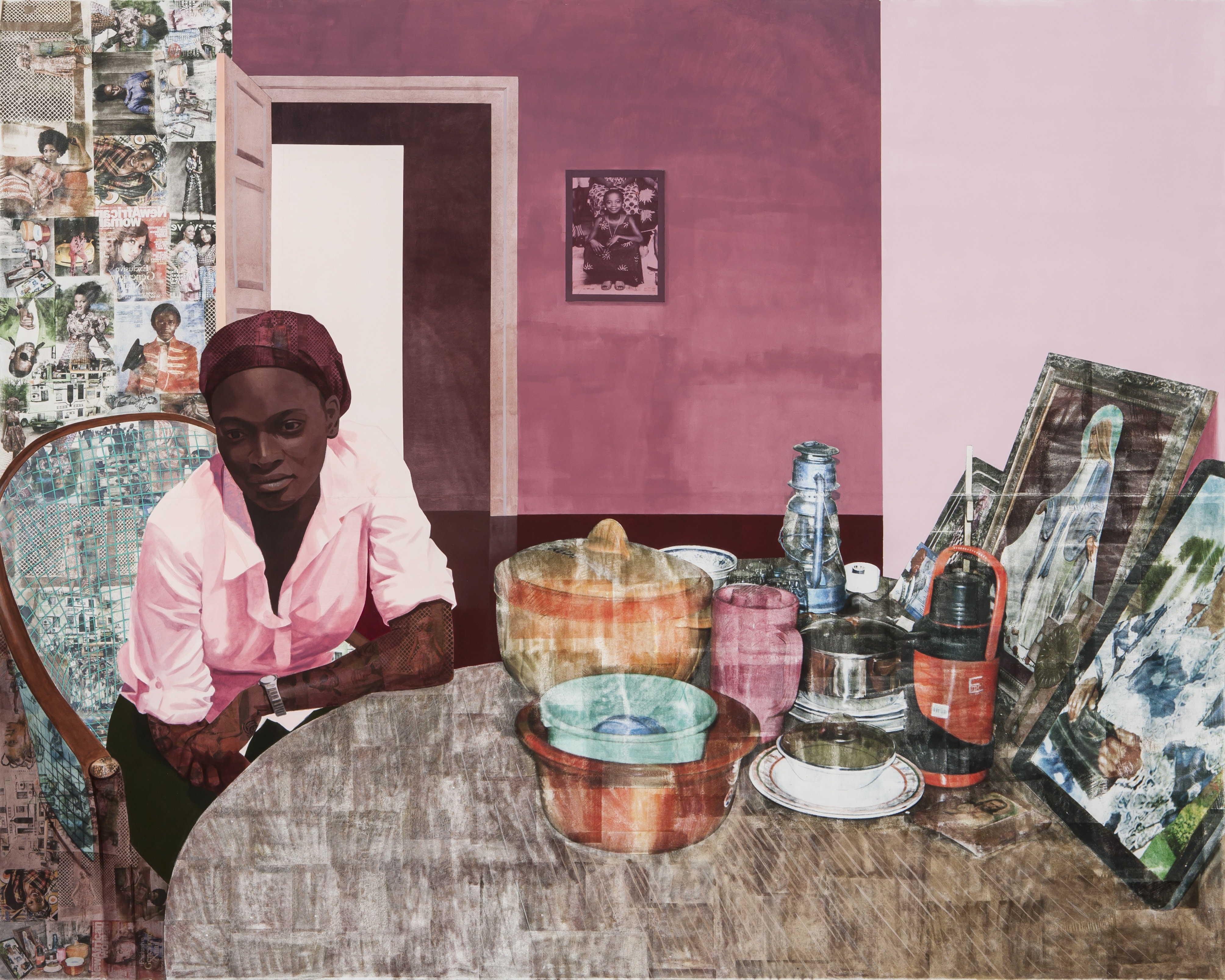

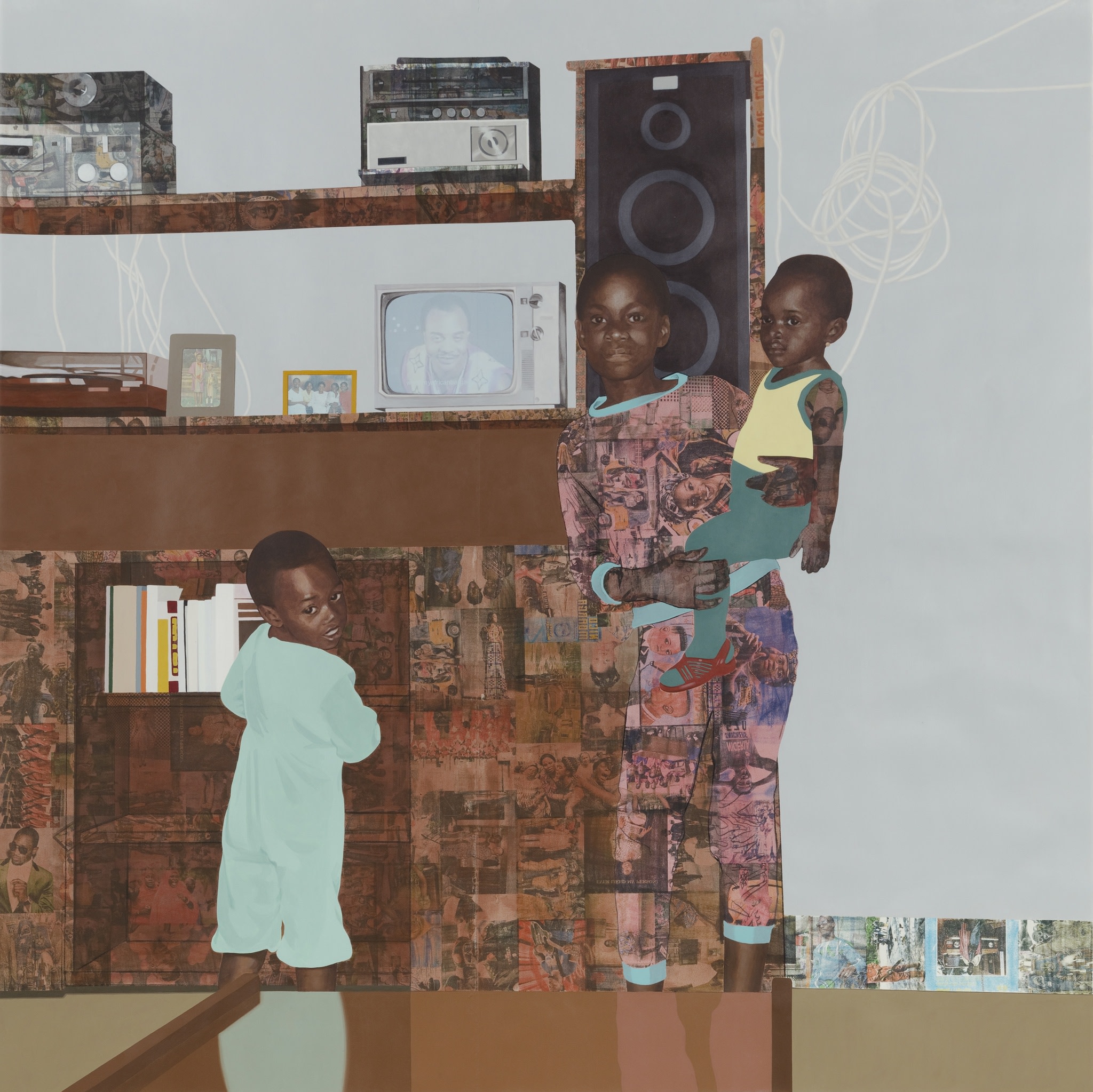

Not long ago, the artist expanded her sources with a call for family photos from old friends. This dragnet brought forth the little boy who is the subject of “The Beautyful Ones” Series #8, dressed in a style of vintage lace that Akunyili Crosby had to research in order to render properly; and the three children in “The Beautyful Ones” Series #9 (pictured ,below), with the older girl carrying the baby.

But the series also signals Akunyili Crosby’s contribution to a stream of literary and political thought that flows through post-colonial African history from the independence era of the mid-twentieth century to the present. At issue is the question of freedom and self-determination, and an ever-renewing realisation that each generation invested with the aspirations of the people seems destined to dash them. World history in recent decades suggests that Africa by no means has the exclusivity of this phenomenon, but African thinkers, stunned by the rapid decay of government so soon after independence in the 1960s and 1970s, were perhaps quicker to face it and describe it.

She first read Ayi Kwei Armah’s The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born in secondary school. Her own series reads as acknowledgment of the problem Armah posed, and as a quiet but assertive response – one of hope sprung eternal, and fresh belief.

Among them was the Ghanaian author Ayi Kwei Armah, whose 1968 novel The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born, morose and poetic, was quickly and deservedly enshrined as a classic of African literature. Akunyili Crosby first read it in secondary school, like so many others in English-speaking Africa, in the ubiquitous Heinemann African Writers Series paperback edition with the orange cover design. Her own series of “The Beautyful Ones” reads as acknowledgment of the problem Armah posed, and as a quiet but assertive response – one of hope sprung eternal, and fresh belief.

In Armah’s novel, the unnamed central protagonist, known simply as ‘the man’, seeks to maintain personal integrity in a society that is falling prey to graft and decay in a time of growing violence. Things do not go well. The man’s insistence on passing up unethical gains rings out of tune with the general atmosphere and alienates those who rely on him, and his situation grows increasingly impossible, to the point where even saving himself and his principles must involve another form of debasement.

The novel’s implicit setting was Ghana, where Kwame Nkrumah – erudite, cosmopolitan, shaped by the Harlem Renaissance and Pan-Africanist thinking – led the movement that secured independence from Britain in 1957, only for his government to grow rigid and corrupt, and fall in 1966 to what would be the first of many military coups. But the themes and imagery applied more broadly, and certainly to Nigeria, where in the same year, 1966, only six years after Nigerian independence, a coup and counter-coup in quick succession decimated the democratic leadership and sundered the country on ethnic lines, opening the door to civil war (the Biafran War of 1967–70) and its devastating toll.

Under the regimes that followed, Nigerian elites gathered back at the trough of booming oil revenues, sweeping the war trauma under the rug. Particularly vile in the mid-1990s under General Sani Abacha, military rule in Nigeria ended only in 1999, when Akunyili Crosby was sixteen. The democratic dispensation that followed has endured, but with deep flaws; the economy is still dependent on oil, and is riddled with inefficiencies that well-connected profiteers systematically turn into opportunities for private enrichment. As much as Nigerian culture is vibrant and its creative exports have blossomed, daily life for most people remains burdened by the same predicament that faced Armah’s hero.

It is both elegant and poignant that “The Beautyful Ones” Series #5, built around the painted restitution of Dora Akunyili’s childhood photograph, features a generous swatch of the commemorative fabric printed on the occasion of her funeral…

This was more than theoretical for Akunyili Crosby’s family, middle-class Igbo people from Enugu – the short-lived capital of breakaway Biafra – shaped by Catholicism, missionary education, and Nigerian universities in their better days. Both parents were medical professionals; Dora Akunyili, a pharmacist and university lecturer, was selected to run Nigeria’s food and drugs agency in 2001, on the basis of her reputation for honesty. In that position, she led an intense and effective campaign against the cartels that trafficked counterfeit medicines, and survived two assassination attempts in the process. (Later, she was briefly a government minister, before dying of cancer in 2014.)

‘She was radical because she had integrity in a system that was unfamiliar with integrity,’ Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, another daughter of Enugu who knew the family, wrote of Dora Akunyili, lauding her as ‘one of the best public servants Nigeria has ever had.’ It is both elegant and poignant that “The Beautyful Ones” Series #5, built around the painted restitution of Dora Akunyili’s childhood photograph, features a generous swatch of the commemorative fabric printed on the occasion of her funeral, with its repeated medallion portrait and the inscription over it that reads ‘Our Icon of Hope Moves On.’

Akunyili Crosby didn’t begin “The Beautyful Ones” with a series in mind, however. The first piece was a one-off, intended to solve a problem of craft that she felt was holding her back. She executed it in several versions, the first one in a larger format that she decided wasn’t ideal, before arriving at the scale, colour values, and energy she required.

The problem was portraiture. By 2012, Akunyili Crosby had emerged from the Yale School of Art and was an artist-in-residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem, a pair of credentials that attested to the calibre of her work and vouched strongly for her potential. Though she still made some traditional paintings, her own visual language had blossomed – triggered, as she has related, by her Yale teachers who could not help but notice the piles of Nigerian magazines and found images she accumulated in the studio and her obvious interest in the world they described.

Works like I Refuse to Be Invisible, 2010, and 5 Umezebi Street, New Haven, Enugu, 2012 (pictured, above), installed not only her image-transfer technique but her approach to group scenes in interiors, in a flattened style that echoed the strategies of Kerry James Marshall, one of her influences. Multiple works staged herself and her husband, Justin Crosby, perfectly expressing the blend of intimate confidence, social querying, and private management of signs and memories that comes when a partner from a very different world comes to meet and stay with the family, culminating in the sublime Nwantinti, 2012 (pictured, below).

Only rarely, however, did her subjects face the viewer head-on. In fact, she was avoiding this. Her initial art-school training at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) had been conservative, emphasising the formal values of the European classical canon, and at Yale she was challenged to make her work less old-fashioned. But portraiture resisted – as she put it, she struggled with flattening the face, and found herself reverting to a soft fleshiness she did not intend. To forestall this tendency, she mostly presented her subjects indirectly, in profile or three-quarter views, but the limitation frustrated her, and she resolved to conquer it.

For inspiration, she turned to the portraits of Diego Velázquez, and in leafing through her book of the Spanish master she halted on his portrait of Infant Baltasar Carlos, 1638–39, held at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, in which the prince, a young child, wears a formal outfit with puffy black breeches in an interior space where the red and gold of a heavy curtain and furniture upholstery frame a darkened room. The prince’s stance brought to mind a family photograph, memorabilia from some special occasion, in which Akunyili Crosby’s oldest sister wears similarly puffy attire. Studying the Velázquez further, she felt that its effectiveness dwelt in its simplicity of composition, and in the strong contrast the artist established between the young prince’s pale hue and the darkness behind – a contrast she could reverse to similar effect.

The play of solid planes and others filled with image transfers puts the architecture slightly off kilter, and the images wash across onto the sister’s outfit, so that she emerges not just from the house but from a whole universe of allusions and signs.

Several versions ensued until Akunyili Crosby was fully satisfied, with “The Beautyful Ones” Series #1c (pictured, above). It contained other decisions that signalled the direction of the series. The gradations of blue on the wall surround a central tone that is intensely familiar from the simple West African houses where just a few shades of paint predominate (another is a kind of pale, minty green).

Dust from the red soil of eastern Nigeria coats the window slats. The play of solid planes and others filled with image transfers puts the architecture slightly off kilter, and the images wash across onto the sister’s outfit, so that she emerges not just from the house but from a whole universe of allusions and signs. The selected images start out historical at the top of the painting, for example with scenes from a visit to late-colonial Nigeria by the new Queen Elizabeth II; they set up internal references across Akunyili Crosby’s personal archive (notice, on the dress at the shoulder, the photograph of the artist’s second sister that becomes the subject material for “The Beautyful Ones” Series #4, pictured below); but they give way, lower down, to colourful album covers, photos of actresses – in the artist’s words, ‘just people who look fly.’

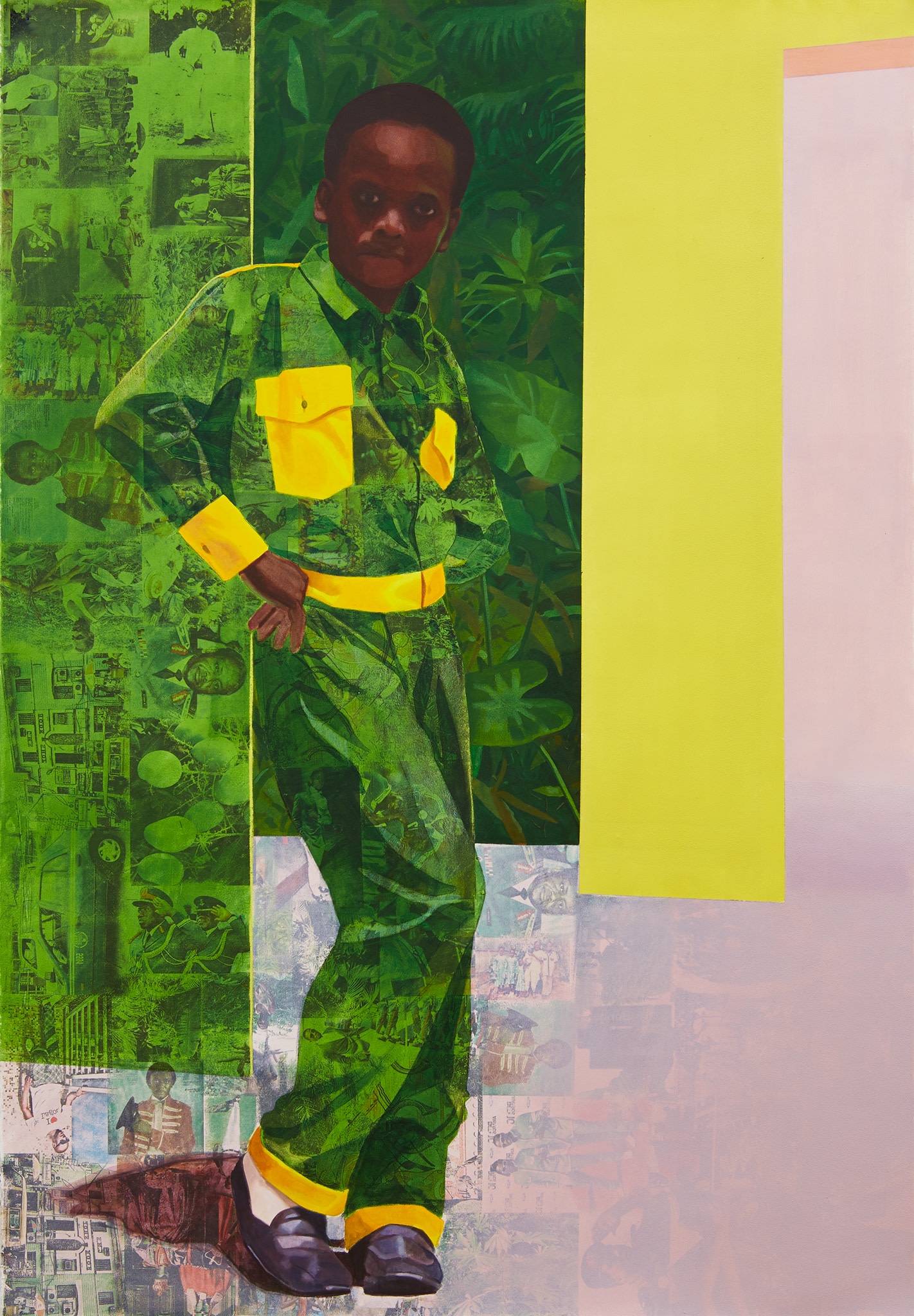

“The Beautyful Ones” Series #2 (pictured below) depicts the artist’s brother in a debonair green party suit with bright yellow pockets and trim, striking a cool, limber pose – this is the Michael Jackson era. The colour scheme and overlay of transferred images make him a gatekeeper between a lush garden and a memory-field where military imagery, drawn from Nigeria’s political history, dominates. The architecture of the scene is quite ambiguous – there are no recognisable interior or building features – but the composition, in its broad lines, works in mirror effect with the first painting. For a moment, Akunyili Crosby thought of them as a duo. Then the series fully took flight, the artist returning to it once or twice a year, in what she describes was a nice break from the even larger, complex, multi-figure works and diptychs that required so much more visual planning.

At the same time, she notes that these pieces, smallish by her standards, introduce their own constraint in the form of a need for economy. In her description, most of the works in the series have taken shape through paring down possibilities. The planning involves establishing the central figure – the portrait subject – then working with drawings and transparencies to design an apt surrounding environment. With a territorial division in place between the figurative painting and drawing, the solid colour fields, and the areas for image transfers, the selection and painstaking application of these images follows. The addition of red, white, or blue washes finalises the tones.

In “The Beautyful Ones” Series #5, the childhood portrait of Dora Akunyili, the image transfers are relatively minimal, so as not to clash with the commemorative fabric. They are limited to the low steps on which she sits, in front of the house. They are also highly targeted: all show strong and accomplished Nigerian women, including the former finance minister Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, the current soul singer Asa, competitors in the 1992 Olympic Games, and Onyeka Onwenu, a popular singer and favourite of the 1980s who often recurs in Akunyili Crosby’s works.

The two girls in “The Beautyful Ones” Series #3 are ones whom Akunyili Crosby spotted and photographed at an event while on a visit to Nigeria; something about each of them reminded her of herself and her friends as children.

Indeed, each ‘Beautyful One’ answers an urge. The two girls in “The Beautyful Ones” Series #3 are ones whom Akunyili Crosby spotted and photographed at an event while on a visit to Nigeria; something about each of them reminded her of herself and her friends as children.

That was enough to qualify them for the exercise. Later, feeling she had left some potential untapped, she revisited the girl who struck her most – hair in tight short twists, arms folded, intent and possibly defiant – for “The Beautyful Ones” Series #7. This time she pushed herself out of her comfort zone to set a street scene, a pure exterior. The impetus came when she came across photographs of Peugeot 504s, the workhorse of 1980s Nigeria roadways, and realised that this was a major icon that she not yet dealt with. The positioning of the car, like the concrete balustrade in the earlier work, solves the problem of not having the girl’s lower body in the source photograph. The Danfo minibuses in the back come from one of Akunyili Crosby’s photographs as well, taken in Enugu. The resulting study, with its dominant yellows, the pink-brown of the transferred image fields, the green of the incidental vegetation, emits an uncanny force. It absorbs the viewer into a quintessential Nigerian urban energy even before we can inspect its details.

In her work, Akunyili Crosby sets herself constraints, then slips them. Her architectures are realistic, until they aren’t. Her image transfers follow an archival method, until they don’t. The children she portrays in “The Beautyful Ones” are her own siblings and those of her friends, but also her mother as a child, and young children she has seen who remind her of something. The rules and the slippage operate in tandem; together they queer both the family and the national archive. She creates a new memory-script that floats across spaces and the fields of signs.

Ayi Kwei Armah has written that he did not come up with the title of The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born until the manuscript was finished. He had learned as a teenager about Egyptian mythology, and was drawn to Osiris, also known as ‘Wn Nefer’, the ‘Beautiful One’. Osiris encapsulated a mode of progress and goodness that was outside the Western confrontational model, a form of moral development and growth that was strictly African. One day, Armah writes, he came across a minibus emblazoned with the inscription ‘The beautyful ones are not yet born.’ He was so struck that he enlisted his friends to look for the minibus and its driver all over Accra, hoping he could take its photograph for the book cover, but never succeeded. But at least he had his title. By serendipity it linked his disappointment at the post-Independence state of affairs with his interior knowledge that true freedom must be locally made, the product of African cultural parameters.

Akunyili Crosby has picked up the challenge. In one work that is not part of the series, but that serves as a precursor, she portrays herself, seated on the floor in a simple house near a radiator (which suggests she may be in the United States), wearing a dress of wax print as reinterpreted by a modern Nigerian designer. Alone, she looks away from the viewer. She is clearly lost in thought. She titled this piece (pictured, above): “The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born” Might Not Hold True for Much Longer.

Then she went out and fulfilled her own prophecy.

This essay was first published on the occasion of the exhibition Njideka Akunyili Crosby: "The Beautyful Ones", held at Victoria Miro Venice in 2019 and appears in the accompanying book.

Siddhartha Mitter is a writer on contemporary art and public culture. He contributes to the New York Times, Artforum, and others.

Watch Njideka Akunyili Crosby and Siddhartha Mitter in conversation, filmed at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, on 8 September 2019 to mark the publication of the book, co-organised by the Whitney and The Studio Museum in Harlem.

About Njideka Akunyili Crosby

Njideka Akunyili Crosby is one of the most distinctive voices of her generation. Drawing on art historical, political and personal references, she creates densely layered figurative compositions that, precise in style, nonetheless conjure the complexity of contemporary experience. Akunyili Crosby was born in Nigeria, where she lived until the age of sixteen. In 1999 she moved to the United States, where she has remained since that time. Her cultural identity combines strong attachments to the country of her birth and to her adopted home, a hybrid identity that is reflected in her work.

Images from top:

"The Beautyful Ones" Series #9 (detail), 2018

"The Beautyful Ones" Series #7, 2018

Mama, Mummy and Mamma (Predecessors #2), 2014

"The Beautyful Ones" Series #9, 2018

"The Beautyful Ones" Series #8, 2018

"The Beautyful Ones" Series #5, 2016

5 Umezebi Street, New Haven, Enugu, 2012

Nwantinti, 2012

"The Beautyful Ones" Series #1c, 2014

"The Beautyful Ones" Series #4, 2015

“The Beautyful Ones” Series #2, 2013

“The Beautyful Ones” Series #3, 2014

Photograph by Njideka Akunyili Crosby (left), Obumneme Akunyili (right)

Photographs by Njideka Akunyili Crosby

"The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born” Might Not Hold True For Much Longer, 2013

Installation view, Njideka Akunyili Crosby: "The Beautyful Ones", Victoria Miro Venice, 11 May–13 July 2019

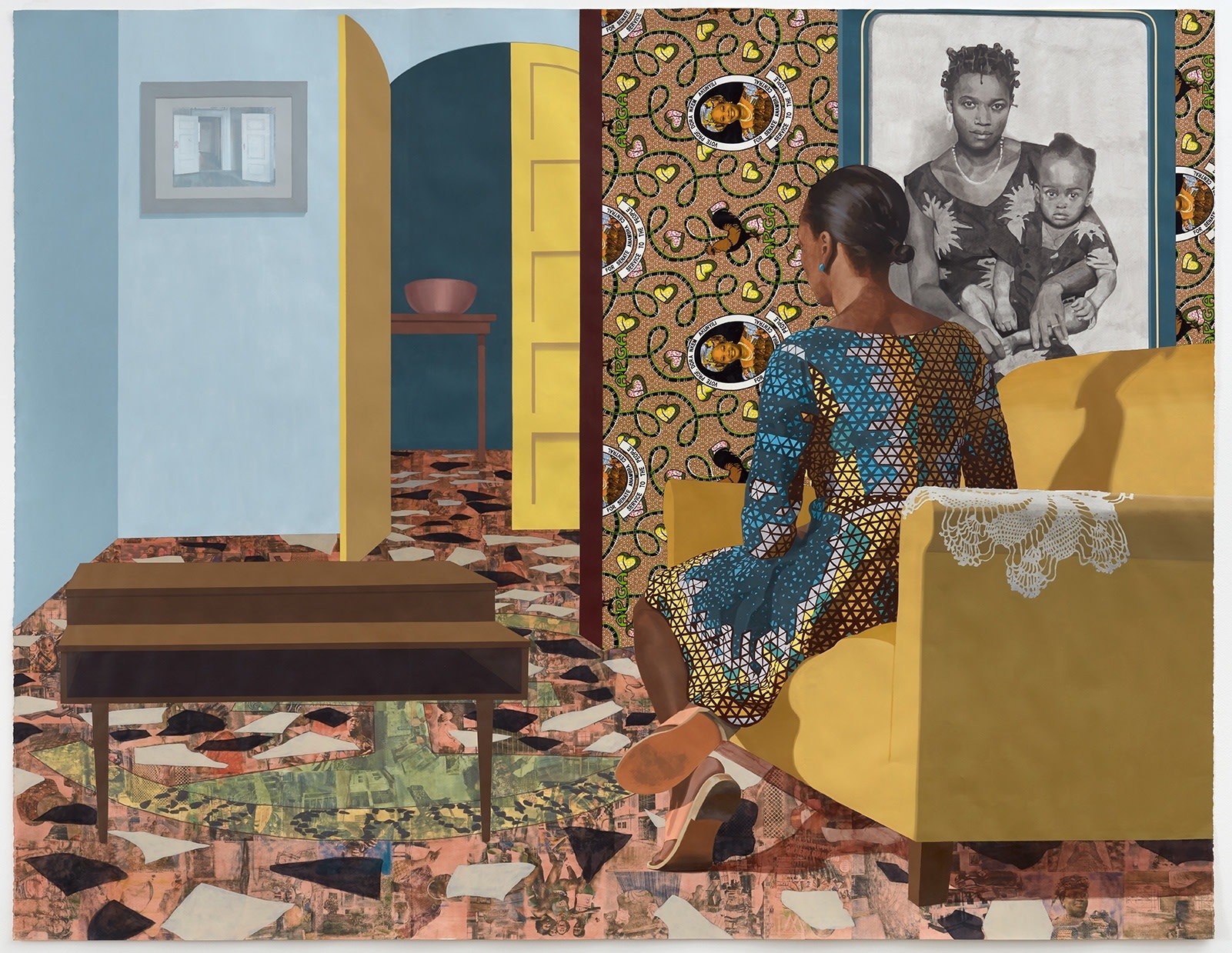

Mother and Child, 2016

All works © Njideka Akunyili Crosby

Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro, and David Zwirner

Text © Siddhartha Mitter