Debbie Meniru explores the interrelation of lived and imagined experience in the paintings of Khalif Tahir Thompson, whose work features in the exhibiton The Stories We Tell.

-

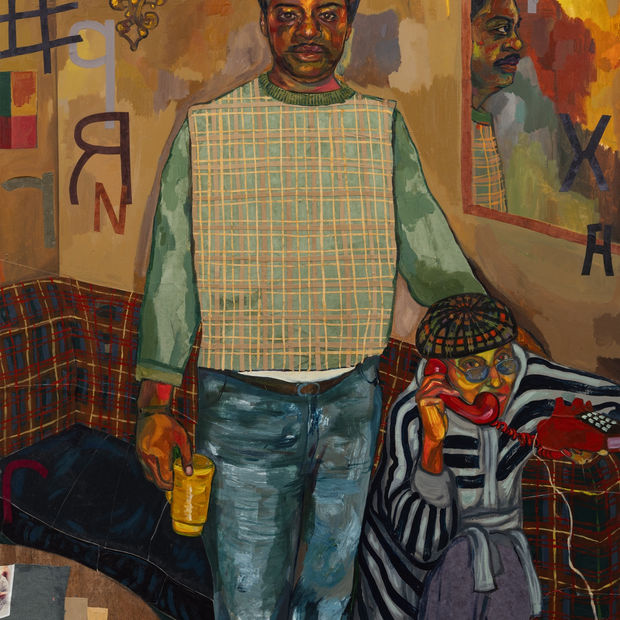

Part memory, part archive and part fiction: the characters that occupy Khalif Tahir Thompson’s paintings form what he terms an ‘imagined experience’. Each begins with an image drawn from his grandmother’s extensive collection of photographs. In Street Scene in Bed-Stuy, we see his grandmother’s house in Brooklyn in 1988, seven years before Thompson was born. This was around the time she won the lottery and built a lavish new home in Florida. After his grandmother died in 2006, her boxes of family photo albums were put into storage for sixteen years until Thompson’s sister was finally able to make the road trip down from New York to Florida to retrieve them.

‘In Street Scene in Bed-Stuy, we see his grandmother’s house in Brooklyn in 1988, seven years before Thompson was born.’

-

Khalif Tahir Thompson, Street Scene in Bed-Stuy, 2025

Khalif Tahir Thompson, Street Scene in Bed-Stuy, 2025 -

Many of the people the artist selects from the photographs are known to him – his grandmother of course, but also his aunt and sister, a distant relative or a family friend. Some Thompson can’t identify. But in all cases, he isn’t particularly interested in capturing a true likeness or reproducing the original photographic image. He cites the paintings of fellow New York-based artist Alice Neel as an influence, and a similar intimacy can be found in their portrayals. But while Neel documented friends, neighbours and peers posing in her home, Thompson’s subjects are less bound to a specific time or place.

-

Khalif Tahir Thompson, Sandy In a Striped Shirt, 2025

Khalif Tahir Thompson, Sandy In a Striped Shirt, 2025 -

More often than not, Thompson’s figures are captured in vibrant domestic interiors full of texture and pattern. Occasionally the characters venture outside and sometimes they leave the canvas entirely. Sandy in a Striped Shirt is, at first glance, a fairly traditional portrait: a woman, dressed casually in a red-and-white striped top and jeans, sits on a wooden chair from Thompson’s studio. I have the impression she hasn’t done this before – pose for an artist – and she clasps her hands together in her lap, slightly unsure. Behind her is her own reflection. It is as though she sits in front of a mirror, and yet there isn’t one depicted. Once you have noticed the strangeness of this, the work shifts. The painting becomes less about the sitter, and more about the space around her. With no mirror edge, there is no boundary between the real space and the reflected one, and the work folds into the realms of fiction. The woman in the striped top is actually based on a photograph of Sandy, Thompson’s aunt, who never sat for him. In the original image, Sandy is sitting in a pickup truck. By reimagining her in his studio, Thompson imbues the work with what he calls a ‘spiritual element’. When people we know pass away, we often learn about other parts of their lives posthumously, through stories, letters and photographs. We see them through the eyes and experiences of others; we imagine other versions of them coexisting with the one we knew. These other selves were there all along but out of sight, playing around the corner, or caught only as a fleeting reflection.

-

Khalif Tahir Thompson, Pink Clouds, 2025

Khalif Tahir Thompson, Pink Clouds, 2025 -

In this way, Thompson’s work floats across an uncertain chronology. Is what we are seeing a piece of history, located in the past? There are certainly hints that we are looking back: retro decor and outdated fashion, a woman talking on a landline. But Thompson is always looking for ways to insert himself into these images. They are acts of interpretation and imagining, rather than attempts to accurately capture memories in paint. Although rooted in the past, his paintings constantly pull us back to the present moment. This push and pull creates the nostalgia which permeates much of Thompson’s work. It is also heightened by his use of colour. He has long been drawn to what he describes as ‘old fashioned’ hues – reminiscent of the 1970s, but earthier: ochres, burgundies, sap-greens and browns. In works like Pink Clouds,he brings together this warm palette with louder, artificial tones: a bright blue wall, a wacky patchwork quilt, a vibrant fuchsia sky. The contrast distorts the perspective of the composition; the view through the window pushes its way back into the room, rather than falling away into the distance. Thompson’s use of colour is inspired by a gamut of other painters from Claude Monet through Reggie Burrows Hodges and Beauford Delaney to Milton Avery and the German Expressionists.

-

Khalif Tahir Thompson, Cashew, 2025

Khalif Tahir Thompson, Cashew, 2025 -

It was collage that got Thompson to start using colour more confidently. In Cashew, he has applied handmade Japanese paper to create the plaid pattern on the man’s top, and papyrus is used in the depiction of the wooden coffee table in the left-hand corner. The material acts as both a ‘real thing’ and an illusion within the painting. It is made strange: why use papyrus for a coffee table? But there is always something odd happening in Thompson’s work: an off-kilter angle, a strange repetition, a story below the surface. In Pink Clouds, we appear to have interrupted a private moment between a man sitting on a bed, hunched over, elbows on knees, and a woman pausing in the doorway. I can’t imagine this was the original image caught on camera. Perhaps they have fought, or is she delivering bad news? I’m desperate to see the next scene but Thompson holds us captive in a single moment.Despite the stillness of Thompson’s figures, the scenes he creates are full of rhythm and repetition. My eyes glide across stripes, dart around brickwork, pulse in quilted squares. Letters and numbers pattern the work. Originally inspired by found text and his interest in characters and form as it relates to language and abstraction, as well as the text that appears in the work of artists such as Kerry James Marshall, the markings here act as disruptors, challenging a simple reading of the composition. The symbols float in the air, decorate walls, deepen shadows and cling to the surface of the canvas. As with the other collaged elements, they challenge the illusory space of the painting, making its physicality come to the fore. These symbols aren’t supposed to be deciphered. They force us to look beyond our desire to decode. To me, they seem like signs of life or perhaps an untold story, while Thompson has described them as ‘visual noise’. Like musical notes, they bring rhythm and sound to the paintings. Not a clear 4/4 beat but moments of syncopation, heady emotional swells and quiet refrains. They suggest more is at play than we are able to comprehend just by looking. Thompson asks us to imagine too.Debbie Meniru

An independent writer, editor and curator based in London. She was previously Assistant Curator of Research & Interpretation at Tate Modern and Tate Britain, London.Text © Debbie MeniruAll works © Khalif Tahir Thompson -

The Stories We Tell: Tidawhitney Lek, Emil Sands,

Khalif Tahir Thompson