The walls in Sarah Sze’s studio are covered by hundreds of images torn roughly into rectangles. Some are pictures of people or landscapes or her earlier work, others read only as colour and texture. Overlapping in clusters, they’re taped and pinned along with sketches, tickets, letters, Xeroxes, peeled paint—the way deranged conspiracy theorists’ apartments look in movies, stretching lengths of yarn to connect one piece of “evidence” to another. I assume it’s planning for one of her famously elaborate installations, where precarious arrangements of detritus subtly reshape large architectural spaces, with strings, wire, paper, projections, reflections, and shadows. This transformation of ephemera into sculptural form has made her one of the most important forces in contemporary art.

She tells me that she started as a painter, studying academically before changing to sculpture, and that she’s been painting on the side, all along.

I’m there to see Sze’s new paintings? Maybe they’re called Flats?—the language hasn’t been set. She tells me that she started as a painter, studying academically before changing to sculpture, and that she’s been painting on the side, all along. She says she’s always thought of herself as a painter making sculptures. Recently she’s started taking these paintings more seriously and is excited to show them. After half an hour I buoyantly suggest we actually go look at them; she takes a beat and smiles. Sure.

We walk into another room with some earlier sculptures. One is a hammock made of blue strings held parallel by two rods, naturally drooping in an arc towards the centre. The individual lines are sparsely and tenderly connected by thin blobs of paint, suspending orange, blue, yellow, green and purple brushstrokes over a concave void. Some of the paint is scattered like petals on the ground below. It reminds me of how Sze has been using paint in recent installations, as though a stroke were made on plastic and peeled off, then draped onto an object so that it curves in space. Paint as coloured matter, like pinned and mounted butterflies. In a different room there is a part of a three-dimensional wire coliseum at chipmunk scale, just over waist high. It has a lot of little paper and plastic screens for catching dozens of miniature and perfectly torqued videos. Often the projection is slightly larger than the screen and makes a glowing frame on the wall behind. She cups her hand in front of the projector’s beam to show me all the little separate videos it carries, like a handful of wiggling pearls. These are signature dynamics of Sze’s sculpture, where the exactly placed objects become forms in space, made mostly of absence, manipulating light and shadow into an environment, so that what is and is not the “sculpture” is impossible to distinguish.

We end up back where we started, in the room papered with hundreds of torn printed images… And it hits me—This is the new work! I laugh, I didn’t realise these are the “paintings”. She laughs too. I marvel at her grace, that she didn’t just say, you already are, when I asked to see the work earlier. She allowed me the space to see it—a major aspect of her sensibility. These flat works—which encompass everything on the wall—look more provisional and rougher than her sculptures, and that is saying something. They’re without the patina of tinkering that accompanies her more elaborate spatial constructions. Because they creep along the walls they might make you conscious of the shape of the room, but are otherwise without her hallmark engagement with three dimensions. They have the extremely shallow frieze-like depth of collaged paper. I just wasn’t prepared to read it as a “painting”. Well, maybe they’re not paintings, she says.

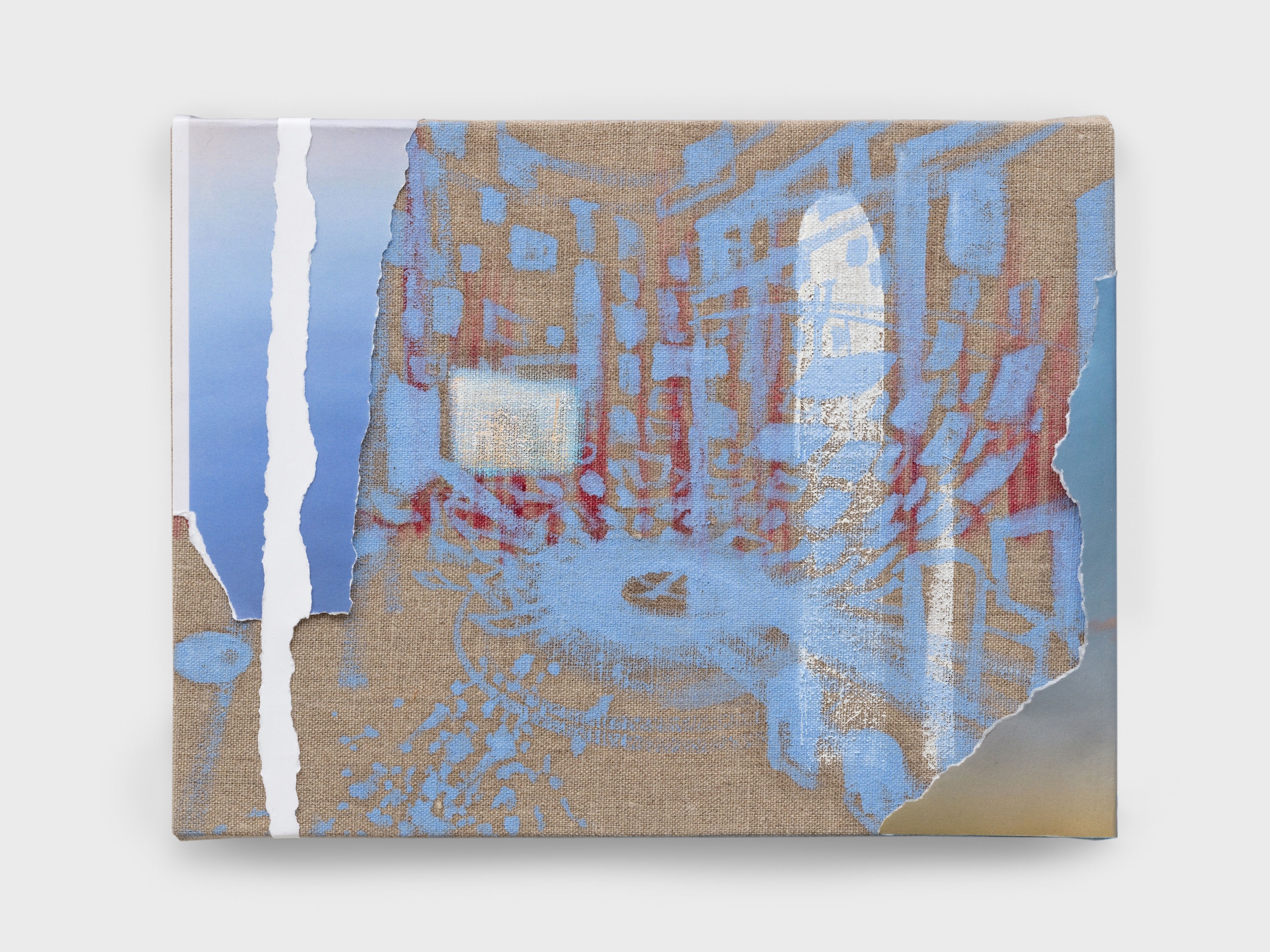

I notice something I didn’t really before: In one area there is a small painting, about nine by twelve inches, nestled among photographs on the wall, fully integrated into the accumulated images around it. A kind of drawing in pale blue paint on tan raw linen, marking out the skeletal planes of an invisible sphere. It’s based on her installation “Centrifuge” (2017) at Haus der Kunst in Munich. The underlying architecture of the room is signalled by reddish underpainting with white shapes that suggest arched windows or doors. On the upper left is pinned a scrap of a printed picture, a gradient of dark to light grey. A white line of semi-autonomous paint, like a jagged zip lifted from a Barnett Newman, is collaged on top. The slight dimensionality of the stretcher casts a shadow on the papers it overlaps—downloaded digital photos of “Centrifuge”, a falcon in mid-flight against an empty sky, and a cryptic black circle on a grey ground, like a dissolving eclipse. I make paintings like that one after the installations are done, Sze says. It’s like a way of processing them, or coming to terms with them another way, pictorially.

Every element is recursive, engaged in a layered call and response, between form, materiality, and meaning.

I ask how she relates to the visual grammar of each of these differently—the oil painting, the sketch, the digital photograph. I understand each of these different media as tools for understanding the others, she says. There is a kind of speed with which we experience images today that creates a kind of melancholia. Every artist I know, if I ask them what they did that day, they will flip through a dozen iPhone photographs to show you. Every exhibition I go to I take digital photographs. I probably won’t ever look at them again, but that act is very much how we live our lives in this moment.

Analysing that one little tableau within the broader panorama of the room shows how the composition works. These digital ink-jet prints on matte paper have a slight fuzz around every form; no line is crisp. Similarly, the way she pulls paint across dry linen creates a raspy edge. It makes you conscious of the pronounced weave of the linen, as the foundation of the image, which uncannily recalls the micro-grid of digital pixelation, almost subliminally. The boundaries between everything are charged. The pale blue paint visually slides into the falcon’s sky below it, though in person the difference between printed ink and oil paint, as vehicles for colour, surface and pictorial information, are more pronounced than their similarities.

Every element is recursive, engaged in a layered call and response, between form, materiality, and meaning. Several of the images are important moments in the history of technical images’ relationship with time. In one mini-tableau you see a print-out of Muybridge’s stop-motion cat running (1887) butted against Harold Edgerton’s famous photograph of a splashing milk drop (c.1935) taped upside down. Just above it is a painting, from an iPhone photograph, of the artist’s daughter sleeping. It’s lightly splattered with grey paint, making a funny rhyme with the milk below. I ask if this melancholy is personal or cultural—I hope it’s both,she says. Each image and object has been cycled through many processes: a photograph of a sculpture turns into a painting which is then photographed, ripped up, sketched on top of, re-photographed, painted on again, and pinned to the wall. Its ending up there doesn’t feel final either, just where it happened to be at this moment, in this arrangement

I think about the recurring image of Sze’s daughter sleeping, and of the falcon suspended in mid-air…. In their stillness and repetition, her “flats” speak more to the human experience of time than the “time-based media” in her sculptural installations…

I tell her it reminds me of something I was doing a few weeks ago visiting the Uffizi in Florence. I found myself taking Polaroids of some paintings there. It seemed like a really stupid thing to do. I had to take them with the flash off, and the low light caused a shutter delay that made them hazy, like starlets in thirties movies. The ephemerality of you taking that little picture of this thing that’s existed five hundred years before you and will exist long after you’re gone—that is the gesture, Sze says. The acknowledgement. It’s sad. It’s a conversation we have with ourselves about time, and increasingly we’re having it with images. Every time we use our phone that way, that’s partly what we’re doing.

But, I say, for me it’s important that it’s not a digital image and it’s not on my phone. The point of the Polaroid is that it’s a little object. Paintings are also objects. The “image” of a painting lives in the material object of the painting, and both have their own parallel lives in the world. The painting will stay the same, has stayed the same, for centuries, but the next time I’m in Florence, I’ll be different and so it will be a different painting for me. I think about the recurring image of Sze’s daughter sleeping, and of the falcon suspended in mid-air, and the milk drop exploding into a coronet on a table. In their stillness and repetition, her “flats” speak more to the human experience of time than the “time-based media” in her sculptural installations, where video loops create shivering stasis.

What Sze’s done in these new works is so wholly of our moment—visually, intellectually, emotionally—that it won’t be fully legible for at least a generation.

We discuss the specific language of technical images, how contemporary the downloaded ink-jet prints look, even of a Muybridge photograph. They have the quality of being downloaded, and we know that that looks right now, she says. We have a very heightened sense of reading imagery in that way. She’s right: Our way of seeing and representing reality is deeply historical in ways we can’t fully understand as we’re living it, and what Sze’s done in these new works is so wholly of our moment—visually, intellectually, emotionally—that it won’t be fully legible for at least a generation. A time capsule of our relationship to images in the early twenty-first century. It must mean something that one of the greatest sculptural minds of our time has reverted to images—the materiality of images as printed and painted objects—as a way of coming to terms with life today.

I walk around her studio taking Polaroids of a few areas. It lets me appreciate the multivalence of her compositions—the formal and structural webbing that moves from one part of the installation to the next, connecting one far corner of the room with its opposite, by the window, through a reappearing image, colour, shape or texture. I’m thinking about how this installation looks here, in her studio, in the afternoon light, and how different it will be installed at Victoria Miro in London. How it will never be exactly like this ever again. And how it makes you aware of that, over and over.

Jarrett Earnest is an artist and writer living in New York City.

About Afterimage

This essay was published to accompany the exhibition Sarah Sze: Afterimage, held at Victoria Miro during the summer of 2018. The exhibition comprised two bodies of work: Images in Debris, 2018, an installation of images, light, sound, film, and objects that study the image in motion; and Afterimage, the first iteration of an ongoing project, which explores how images function as tools to make sense of the world. Comprised of multiple layers of paint, ink, paper, pencil, prints, objects, and wood, these works both re-frame and refract the collision of images we are confronted with daily.

Afterimage film

'I’m interested in the idea of how something is seared into your memory. We have all of this information… How does something stick with you?' Hear Sarah Sze discuss the process of creating the site-specific works in her 2018 exhibition at the gallery.

About Sarah Sze

Since the late 1990s, Sarah Sze has developed a signature visual language that challenges the static nature of sculpture. Sze draws from Modernist traditions of the found object, dismantling their authority with dynamic constellations of materials that are charged with flux, transformation and fragility. Captured in this suspension, her immersive and intricate works question the value society places on objects and how objects ascribe meaning to the places and times we inhabit.

Sze represented the United States at the Venice Biennale in 2013, and was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship in 2003. The artist has exhibited in museums worldwide, and her works are held in the permanent collections of prominent institutions including The Museum of Modern Art, the Guggenheim Museum, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; The Fondation Cartier, Paris; The Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

Film: the artist's 2019 TED talk, in which she takes the audience on a kaleidoscopic journey through her work.

Images from top:

Sarah Sze's New York studio, 2018

Afterimage, Blue with Fingerprint (Painting in its Archive) detail, 2018

Sarah Sze's New York studio, 2018

Afterimage, Grey and White and Rainbow Spectral (Painting in its Archive) detail, 2018. Oil paint, acrylic paint, archival paper, UV stabilizers, adhesive, tape, ink and acrylic polymers, shellac and water based primer on wood. Installation: 112 x 139 x 4 cm, 44 1/8 x 54 3/4 x 1 5/8 in

Afterimage, Rainbow Disturbance (Painting in its Archive) detail, 2018

Afterimage, Rainbow Disturbance (Painting in its Archive), 2018. Oil paint, acrylic paint, aluminum, archival paper, UV stabilizers, adhesive, tape, ink and acrylic polymers, shellac and water based primer on wood. Installation: 262 x 550 x 12 cm, 103 1/8 x 216 1/2 x 4 3/4 in. Installation view at Victoria Miro

Afterimage, Blue with Fingerprint (Painting in its Archive), 2018. Oil paint, acrylic paint, archival paper, UV stabilizers, adhesive, tape, ink and acrylic polymers, shellac and water based primer on wood. Installation: 275 x 452 x 14 cm, 108.3 x 178 x 5.5 in. Installation view at Victoria Miro

Polaroids by Jarrett Earnest

Afterimage, Screen with Blue Sun (Painting in its Archive), 2018. Oil paint, acrylic paint, archival paper, UV stabilizers, adhesive, tape, ink and acrylic polymers, shellac and water based primer on wood. Installation: 154 x 569 x 6 cm, 60 5/8 x 224 1/8 x 2 3/8 in. Installation view at Victoria Miro

Sarah Sze: Afterimage installation view at Victoria Miro London, 2018

Text © Jarrett Earnest

Sarah Sze's studio photography: Christopher Burke Studio, New York

Artworks and installation photography: Angus Mill, London

All works © Sarah Sze