There are plenty of known knowns in what John Kørner has recently painted: ships and trees, men and women, crocodiles and birds, town and country—and most apparently in ‘2006 Problems’, factories and bicycles. These are modern things that we know we know. And as this commandeered logic continues, we know there are some things we do not know (known unknowns), and still others we don’t yet know we don’t know (unknown unknowns). It’s the known unknown phenomena that belongs to the realm of Kørner’s sustained symptomatology of problems. Visible in paint as coloured blot marks shaped like elongated eggs or dropped-in droppings, problems often line up in Kørner’s works as if notes on a musical stave or blobs of clay on wobbly shelves, latent undifferentiated tissue that’s waiting to become more specific. Of course how to paint a problem must have been in itself a problem. We may presently be dealing with the problems of this year, or equally, it could be that there is a host of two-thousand and six of these quandaries. Kørner makes paintings and painted ceramics, while, as he insists, he is not really a ‘proper’ painter. His often vast canvases are foremost a way of communicating through a very direct means and are only paintings later, almost by coincidence. All of this is, needless to say, problematic.

Problems often line up in Kørner’s works as if notes on a musical stave or blobs of clay on wobbly shelves…

In common with the paintings of his Danish contemporaries Tal R and Kaspar Bonnén, Kørner’s works are gregarious and effusively active things. Furthermore, the painted elements in Kørner’s exhibitions are often deployed as scenographic components, and become clear participants and knowing interlocutors in the conditions of their viewing. Recently, at ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum, Århus, for example, Kørner assembled an environment in homage to a bank, with an adjoining lobby arcade. Within this structure painted canvases were suspended on wires behind glass and brightly lit with spotlights. Replete with a tinny speaker that emitted faint electrocalypso muzak, the setting was both spectacular and vernacular in its borrowing of a familiar and tacitly showy environment for display and the showing-off of merchandise. The colour of Kørner’s paintings behaves too in a habitual and up front way, while materially the effects of the acrylic paint seem more at home with the artisanal glossy glazes and chemical patinas of his decorated ceramics than with the history of canvas-based practice. The signature coruscating yellow, that of extreme rain gear or cautionary road markings, is the essence of high visibility. Together with this yellow’s stain-like counterpart purple—coincidentally both colours of the chemical iodine in different states—the paintings operate in an intrinsic idiom of potently direct communicative chromatics. Of course the natural world—and folklore—know this behavioural application of colour intimately. And it’s perhaps no surprise that the iconic red-and-white poisonous fungus Amanita muscaria, notorious for its psychoactive and mystical properties, finds perfect conditions for growth in Kørner’s oeuvre, occurring in a number of his ceramic protuberances.

The signature coruscating yellow, that of extreme rain gear or cautionary road markings, is the essence of high visibility.

There is a spirit of frank lucidity to Kørner’s enterprise (where even things that are problematic try their best to be clearly visible) that resists unnecessary obscurantism or any notion that the paintings or the artist somehow have access to priviledged information. What do they think? What do you think? What is the chap on the bicycle thinking? What’s the problem? The video that Kørner made recently with Morten Lindberg, called My Seven Best Paintings, is a wonderful summation of the artists mission. It is not an artwork, but more like a series of public broadcasts in which Kørner brings seven different canvases along with him accordingly on seven different encounters, making a short introduction and inviting questions and dialogue from distinct groups of people. In an auditorium setting, a painting of a bicycle—which he suggests to the assembled students could in fact be a spaceship—acts like a visual aid for what might pass for some kind of motivational presentation or hokey product demonstration. In another segment, a painting of a sunset over the sea sits upright in a wooden boat as it bobs on the water. Kørner’s own skiff tootles in from camera right and he drops anchor, addressing us (and the local birds) as if he is introducing a report about fishing quotas. Then there is the group of kids at a zoological museum, who naturally seem more interested in the sticky buns and fizzy pop laid out for them in front of a walrus diorama, than Kørner and the exuberant painting that sits on the floor with them. And in another segment, any artist’s most challenging commentators—the parents—have an audience with their artist-son and acrylic-on-canvas friend called Festival, both of who barely fit through the door of their apartment.

In another work, a couple discuss their problems while riding a bike; not least, it would seem, the problem of how not to fall off it.

In ‘2006 Problems’, problems emanate from the space in between the two workers having a picnic and jamming on their instruments in one painting. Problems are a conceit that sprout like errant thought bubbles or populate buildings, the known and the unknown coexisting. In another work, a couple discuss their problems while riding a bike; not least, it would seem, the problem of how not to fall off it. Like the famous sentimental scene from Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid (1969) in which Paul Newman as Cassidy and Katherine Ross’s character Etta Place share a bicycle interlude from the Western action together—to the anachronistic soundtrack of Burt Bacharach’s ‘Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head’—bicycles in this and other painted scenes become devices by which characters explore a similarly gently psychedelic respite from duty.[1]

The factory is a big problem. The factories in Kørner’s settings are both monstrous behemoths and reassuring, exemplary architectural stalwarts. Employing and providing, and defining leisure-time landscapes via negativa, the factories are necessarily problematic but always unwaveringly modern. They are of course not today’s brightly-coloured metal boxes of enterprise estates, but upright factories belonging to the town, proudly sporting smoking chimneys like beached ocean liners. Kørner’s realm of modern problems is frequented by many such introductions to the badges of civilisation. The schools, the post offices, job centres, museums, hotels and banks which riddle the paintings each occur as indicative services for a developed society. The factory, representing the fundamentals of a manufacturing economy, feeds them all. Akin to the historical fashion in many aspirational European societies for parsing the services, trades and characters of everyday life into painted ceramic tiles—showing the weaver weaving, the miller milling, the baker baking, for example—Kørner’s painted scenes reflect on the constitution of societies defined by work, as well as the cultural history of industry, with a supplementary psychology of problems.

The factories in Kørner’s settings are both monstrous behemoths and reassuring, exemplary architectural stalwarts.

Though the factories might look like they belong to a bygone industrial era, they do not appear so because of any sense of nostalgia or because they are in any conventional sense part of historical scenes, but because, put simply, this is what factories look like. Something like anachronism seems to inhabit too the style of dress of the paintings’ characters. The ‘vagabond’ character with the top hat, for example, a regular gentilhomme in Kørner’s scenography, might seem to be a fi gure from the past—or a distant cousin of the hatted fellow Peter Doig has painted in Metropolitain (2003) and other works. Yet he is foremost a representative citizen of the civil society that Kørner imagines, who works at the factory together with the woman who we now know is his wife. The period in which the paintings are set is not distinct in the same way that the specific identity of its folk—their faces obscured by tangles of hair or out-of-focus paint—remains beyond the knowable.

The period in which the paintings are set is not distinct in the same way that the specific identity of its folk remains beyond the knowable.

If John Kørner’s works seem both insistently direct and yet quite nonsensical, modern but somehow timeless, and so on, and are entangled in a whole ecology of problems both interpersonal and philosophical, then the most fitting way to approach them may be as a part of a tradition of ’pataphysics.

The French absurdist writer and anti-philosopher Alfred Jarry coined this simple-yet-esoteric science of imaginary solutions in 1893, supposing a supplementary universe where everything is exceptional. Following fellow Jutlander, painter and ceramicist Asger Jorn and his 1961 elaboration of Jarry’s ’pataphysical postulations, Kørner and his painted realm confirm that there is no merit in having everybody believe the same thing. In encompassing what is possible and not possible, problematic and not problematic; the artists own judgement and our judgement; known knowns, known unknowns and unknown unknowns alike, all as equivalents, we can revel in liberated contradictions and exceptions. Each to their own problems! As the now absent oracle of the illuminatingly absurd Syd Barrett chronicled in the song which serve as our coda here—and which could be the soundtrack for this free-wheeling interlude of our own, or the vagabond’s lullaby to his new wife—what better a premise could there be for a bike ride?

I’ve got a bike,

You can ride it if you like

It’s got a basket, a bell that rings

And things to make it look good

I’d give it to you if I could, but I borrowed it

You’re the kind of girl that fits in with my world

I’ll give you anything, everything if you want things

I’ve got a cloak it’s a bit of a joke

There’s a tear up the front it’s red and black

I’ve had it for months

If you think it could look good then I guess it should

You’re the kind of girl that fits in with my world

I’ll give you anything, everything if you want things

I know a mouse and he hasn’t got a house

I don’t know why I call him Gerald

He’s getting rather old but he’s a good mouse

You’re the kind of girl that fits in with my world

I’ll give you anything, everything if you want things

I’ve got a clan of gingerbread men

Here a man, there a man, lots of gingerbread men

Take a couple if you wish, they’re on the dish

You’re the kind of girl that fits in with my world

I’ll give you anything, everything if you want things

I know a room of musical tunes

Some rhyme, some ching, most of them are clockwork

Let’s go into the other room and make them work [2]

1. Incidentally, Kørner’s native Copenhagen is one of the most bicycle friendly cities in the world, with over a third

of residents pedalling to work.

2. Syd Barrett, ‘Bike’, Pink Floyd, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, 1967

This essay was originally published to accompany the exhibition John Kørner: 2006 Problems, the artist's first solo exhibition at the gallery, which was held at the gallery November–December 2006 and featured paintings and a specially conceived installation.

Max Andrews is a writer, curator and co-founder of Latitudes, Barcelona, Spain. He is a contributing editor of frieze.

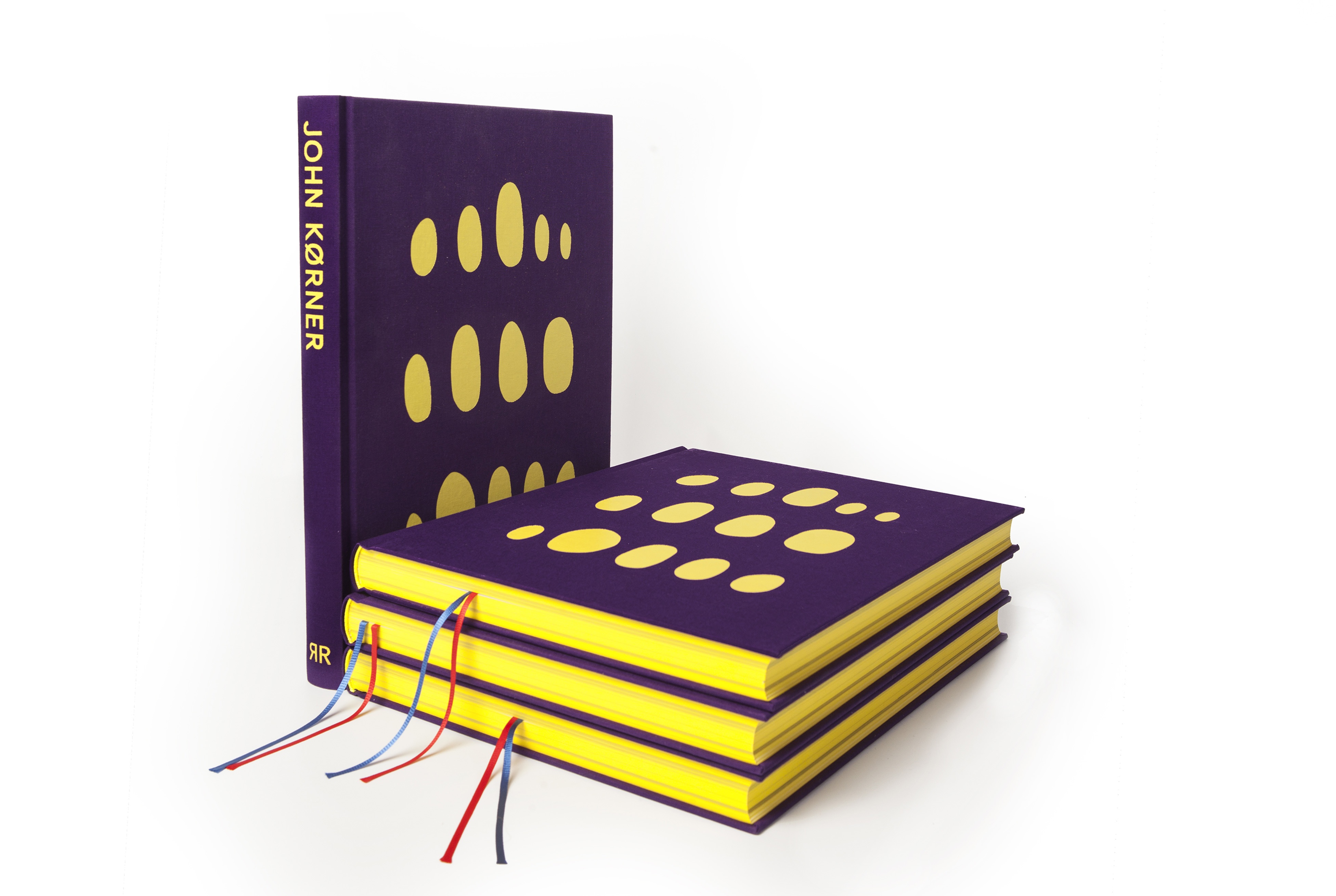

In 2018, Roulette Russe published the most comprehensive monograph on the artist to date. This 280-page hardback book is richly illustrated with works from throughout Kørner's career and features an interview with the artist by curator and Director of Copenhagen Contemporary, Marie Nipper, and essays by Oliver Basciano, International Editor of ArtReview, and Max Andrews, Contributing Editor of Frieze

About John Kørner

Born in Århus, Denmark in 1967, John Kørner lives and works in Copenhagen. He has had solo exhibitions at international institutions including Konsthall 16 / Riksidrottsmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden (2019); Helsinki Contemporary, Helsinki, Finland (2018); Museum Emma, Espoo, Finland (2018); Brandts, Odense, Denmark (2016); Museum Belvedere, Oranjewoud, Netherlands (2016); Herning Museum of Contemporary Art, Denmark (2003, 2013); The Workers' Museum, Copenhagen, Denmark (2011); ARoS Århus Kunstmuseum, Denmark (2006) and Moderna Museet, Sweden (2005).

His work is in major collections including Arken, Museum of Modern Art, Denmark; ARoS, Århus Museum of Art, Denmark; HEART – Herning Museum of Contemporary Art, Herning, Denmark; Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden; National Gallery of Canada – Musée des beaux-arts du Canada, Canada; National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen, Denmark; Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Copenhagen, Denmark; Rubell Family Collection, Miami, USA; Saxo Collection, Saxo Bank, Copenhagen, Denmark; Statens Museum for Kunst – SMK, Denmark; Tate Gallery, UK.

Works from top:

Mr and Mrs Smith at Work (detail), 2006

27 Problems, 2006

Music and problems, 2006

Conversation, 2006

Two men bicycling, 2006

Man and wife, 2006

Mr and Mrs Smith at Work, 2006

Leaving the sun, 2018

All works © John Kørner, courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro